The Cousin Kings

In 1914, war was looming in Europe. This is a familiar story to many: the governments of Europe’s great powers (particularly their kings) had been itching for a good fight and were looking for any chance to go to war. The assassination of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand provided the perfect opportunity, causing the entire continent to ignite and become embroiled in the Great War due to a complicated web of alliances. This is the story we all know, and while there is certainly truth to the tangle of European alliances, this idea of war mongering monarchs has led to widespread misconception of the great men who ruled during this time — particularly the kings of Britain, Germany, and Russia.

These three monarchs — the King, the Kaiser, and the Tsar — were not only the leaders of the most powerful nations in the world at the time, but they were also cousins and close friends. King George and Kaiser Wilhelm were both grandsons of the late Queen Victoria. The German Kaiser’s British heritage led to an interesting relationship between the two countries. While he dearly loved his English mother, he resented the English doctor who watched over his father in his final years.

The Kaiser initially hoped for what he called an “Anglo-Teuton Hegemony,” an alliance between the German and British Empires. This might have worked, had it not been for the Kaiser’s great “Daily Telegraph Affair.” In 1909, the Kaiser was interviewed by the British newspaper Daily Telegraph. Unfortunately, Wilhelm was notoriously bad with words and allowed himself to make some less than complimentary remarks about the British. To make things worse, he asked his Chancellor, Bernhard von Bülow, to proofread his interview before submitting it. Von Bülow didn’t feel like looking over the Kaiser’s response and sent it in anyway, accidentally painting Wilhelm as a crazy, anti-British tyrant. Sadly, this would sour relations between the two cousins. Once the war was over, George regarded his former friend as “the greatest criminal in history.” Nonetheless, the King opposed the trial of the Kaiser, instead allowing him to live out his exile in peace.

Much fonder than the relationship between King and Kaiser was that between Kaiser and Tsar. Although Wilhelm and Nicholas were more distant cousins (third as opposed to first), they were famously close friends. In 1905, the two monarchs met without permission of their respective governments to discuss a treaty. Although their governments promptly and thoroughly rejected their efforts, this did not hamper their relationship.

Nor did war. In fact, even while Germany and Russia were engaged in brutal conflict, the monarchs maintained regular and friendly contact. The so-called “Willy-Nicky Correspondence” chronicles the war through the eyes of these two cousins. They referred to one another by the endearing nicknames “Willy” (for the Kaiser) and “Nicky” (for the Tsar) as a sign of friendship despite the conflict. The letters and telegrams show both of them desperately trying to avoid escalation.

The men’s friendship lasted up until Nicholas’ violent murder in 1918 during the Bolshevik Revolution. After the war, Wilhelm claimed that he did everything in his power to rescue his cousin, demanding the post-Revolution Russian government immediately deliver the royal family to German territory, safe from harm.

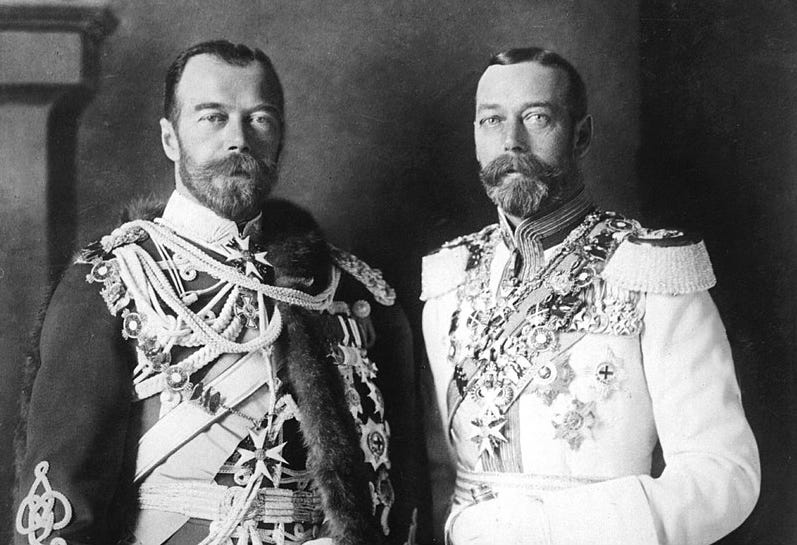

The final, and perhaps closest, relationship of the cousin kings was that between King George and Tsar Nicholas. Not only were they both grandsons of the Danish King Christian IX, but they also looked strikingly similar. They looked so much alike, in fact, that it was not uncommon for the two to secretly sneak off and switch uniforms while at a party, just to see how long they could impersonate each other.

George and Nicholas’s close friendship was reflected in their countries’ foreign policy, as Britain and Russia were close allies leading up to the war. When revolution came to Russia, George extended an invitation to host Nicholas and his family in England. The King’s government even went so far as to have MI1 (British Military Intelligence) plan an elaborate extraction plan to rescue the Romanovs. Alas, the Bolshevik revolutionaries were too powerful for the Tsar to be rescued, and George was unable to help save his cousin.

The stories of the cousin kings mostly ended in tragedy. Nicholas was murdered alongside his family; Wilhelm was shamefully deposed; only George was left on the throne by the time the Great War ended. As for their friendships, the Tsar maintained his relationship with the others until his death, but the King and Kaiser were steadily estranged.

This very tragedy, however, is a testament to the true character and intentions of these men. Instead of warmongers eager to fight each other, we see three cousins who, due to the crumbling world around them, lost their grasp on a once-strong brotherhood. The love between these cousin-kings was not enough to save the world from the most destructive war the world had ever seen. It was, however, strong enough to offer a reprieve from the cutthroat politics of the time — both for each other and for future historians. We could look back at the friendship of these kings and think, “What if they had avoided that war?” But perhaps it would be better to take from this story a warning against neglecting friends and family in favor of private interests. While our personal matters morph and change day by day and year by year, the bonds we share with others can bring strength and peace even in the face of overwhelming difficulties.