A Fingernail in the Clay

All of history, properly viewed is this: marks of persons, that reveal, like a barely opened door, a deep and human world, into which we may glimpse but never enter.

One rarely turns to ancient Mesopotamian writing for feelings of human warmth. Their writing can seem as arrogant and formal as the statues of the kings of Babylon or Ahurbanipal’s horrid commissions of his own atrocities.

This style is imposing when we read Hammurabi’s monumental preface to his code of laws (some 600 words describing semi-divine deeds and titles), because his work really was monumental and worthy of admiration. Hammurabi may not have “conquered the four quarters of the world” or been commissioned by Anu and Bel to “bring about the rule of righteousness in the land, to destroy the wicked and the evil-doers so that the strong should not harm the weak”, but his granite pillar gave a method to justice, and his meticulous concern for details laid the foundations for everything from due process to way to worker’s compensation. A monumentum aere perrenius indeed.

On lesser lips, this arrogance is quite ridiculous. When Sulgi, “god of manliness, the foremost of the troops”, boasts that he is “a powerful man who enjoys using his thighs”, I cannot keep a straight face. Mesopotamian arrogance trickled down from kings to scribes, all the way to animals. In the Debate between Bird and Fish, we read such lines as:

“I am Fish. I am responsibly charged with providing abundance for the pure shrines. For the great offerings at the lustrous E-kur, I stand proudly with head raised high!”.

Ancient fish apparently possessed not only a sense of religious duty, but also legs (a point in favor of young-earth evolutionism).

Yet, while researching the Ancient Near East this summer, I found myself strangely moved. What moved me was a small detail about Babylonian legal documents.

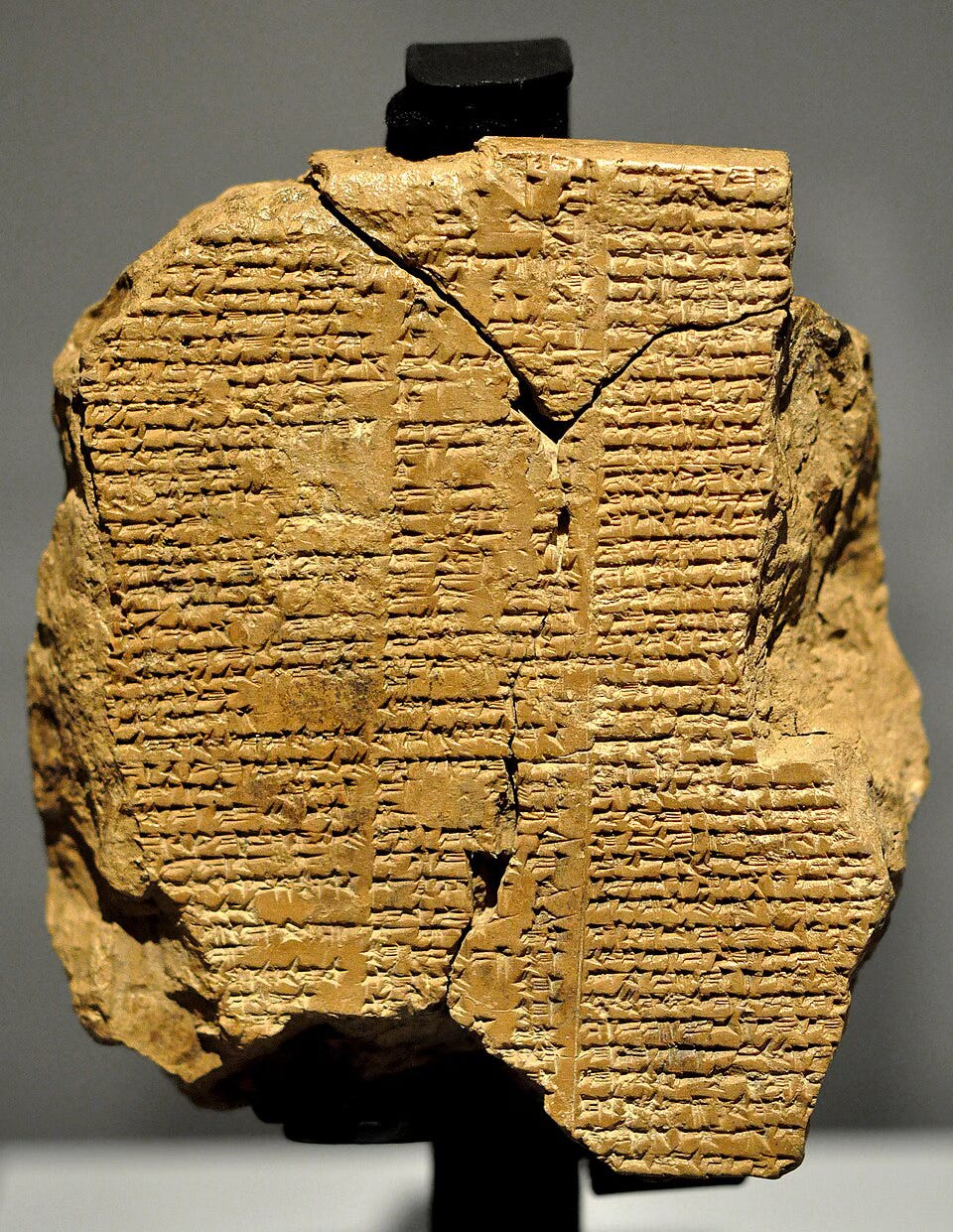

For Babylonians, seals served much the same way that signatures, passwords, or even Social Security numbers do today. They were a person’s unique imprint. This mark was affixed not just to legal documents and letters, but even to sealed doors as proof of the last person to enter and exit.

But the poor could not afford the finely made seals of kings and magistrates. They used simpler marks: the hems of garments and their own fingernails. They put a part of themselves in the clay of tablets. The clay, baked by fires, still bears these human marks some three thousand years later.

It is this image of humanity that is so moving. The person who laid their finger in wet clay must have used that same finger to work, to eat, to pray, perhaps to curse. They were not, perhaps, so different from me. The gulf of millennia is bridged by a piece of baked clay.

But there are other ways to leave an image of yourself in clay. The writing stylus, just like the fingernail, leaves the record of a man. The scribes, too, put something of themselves into the tablets that we can still read. Instead of a bodily mark, they impressed their fears, joys, and griefs.

Consider the following passage from the Epic of Gilgamesh. Gilgamesh has lost Enkidu, the only man who was his equal and therefore his only friend. In his grief, he turns to thoughts of his own death and wanders in search of the cure for death:

“Why should I not wander over the pastures in search of the wind? My friend, my younger brother, he who hunted the wild ass of the wilderness and the panther of the plains, my friend, my younger brother who seized and killed the Bull of Heaven and overthrew Humbaba -in the cedar forest, my friend who was very dear to me and who endured dangers beside me, Enkidu my brother, whom I loved, the end of mortality has overtaken him. I wept for him seven days and nights till the worm fastened on him. Because of my brother I am afraid of death, because of my brother I stray through the wilderness and cannot rest”.

This passage is moving, but the modern age has blunted its power. Our world no longer ends at the walls of Uruk. We are transfixed by Gaza, Ukraine, and Sudan, and there is only so much room for the grief of a mythic king. I, for one, cannot weep for an imaginary Gilgamesh. Yet when I read this passage, I do not believe we are simply reading about a man who experienced the depths of friendship and feared his own mortality. I believe that they were written by such a man. Could the author have guessed what it was to feel grief? Did he simply imitate fear? Perhaps in this age, he could learn to, as the production and broadcasting of tragedies (real or imagined) make up a lively industry. But not then.

No, he knew. Death was no stranger to this scribe. The words he gave to Gilgamesh did not proceed from mere speculation.

Perhaps this is why this Sumerian epic was preserved, some thousand years later, by the Babylonians. A man from a people they had conquered had written a story a thousand years before in a language totally alien to theirs. And in that man, the Babylonians saw themselves.

It is this man, whoever he was, who moves me. Who was his Enkidu? What struggles did they face together? How did he grieve? I do not know. But that he knew friendship, loss, and fear, I can know.

All of history, properly viewed, is this: marks of persons that reveal, like a barely opened door, a deep and human world, into which we may glimpse but never enter.